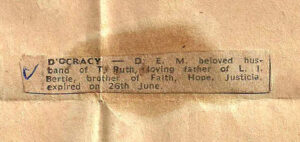

“O’Cracy, D E M, beloved husband of T Ruth, loving father of L I Bertie, brother of Faith, Hope and Justicia, died on June 25.”

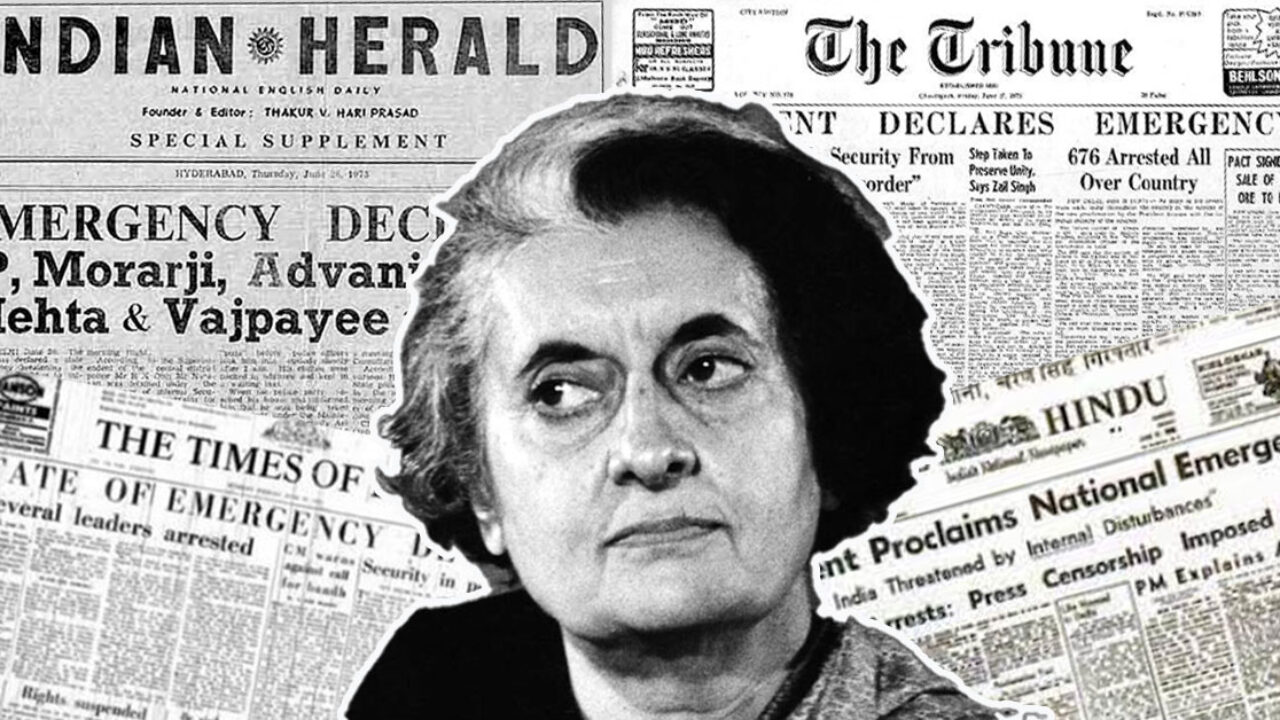

This particular ‘death’ note had appeared in the obituary column of The Times of India on June 26, 1975. It was the most celebrated item of that time which was anonymously placed in the newspaper. The creator of this; an outside journalist, Ashok Mahadevan had to shave his beard to escape detection post the TOI’s submission to a police inquiry.

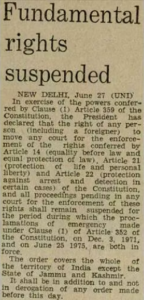

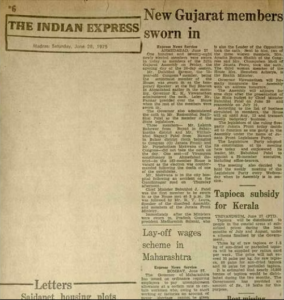

This is just one instance, there were many instances which followed during the era of press censorship when the freedom of speech was curtailed to the lowermost level. The Indian Express had carried a blank editorial in June 27 edition. In response to anti-government protests, India implemented the strictest press censorship since Independence on June 28, 1975 under the leadership of the then Prime Minister, Indira Gandhi.

What the Press had to ‘Adhere’ to?

For journalists all around the nation, the Indira Gandhi administration set basic ground rules and provided them with “guidelines” to abide by. According to a few reports, by the time the editors and journalists learned the full extent of the situation in the country, many leaders and activists had already been imprisoned.

Among numerous guidelines, one was that “newspapers will support the Chief Press Adviser by suppressing it themselves where it is obviously dangerous.” Referral to the closest press adviser may and should be made when there are questions. The foreign media was rushing to report on the situation in the country since the local media was being attacked during the 21-month emergency period.

It was advised to the Indian media not to believe the rumours. The Chief Press Advisor, a post designed to censor the news, required all national publications to obtain authorization before publishing any articles.

The Threats and Arrests

The majority of newspapers and publications in the mainstream media were subject to the wrath of Emergency. Big publishers like Himmat, Janata, Frontier, Sadhana, and Swarajya among many others were slashed by the censors’ scissors. Some received threats to be dropped from publications, while others received jail time. First to express their disapproval through their publications were The Indian Express and The Statesman.

The editorial pages of The Indian Express and The Statesman were empty in protest. Other publications quickly followed this action as well. Journalists from The Times of London, The Washington Post, and The Los Angeles Times were reportedly kicked out, according to IE. After receiving threats, the journalists for The Guardian and The Economist flew back to the United Kingdom.

The BBC’s voice, Mark Tully, was also dropped by the network. The Home Ministry reports that almost 7,000 journalists and media workers were detained in May 1976.

Fight for Freedom

The police detained journalist Kuldip Nayar for participating in a demonstration in Delhi against the emergency. The leaders of the opposition were working for the same cause all over the nation. One of them was LK Advani, a seasoned member of the Bharatiya Janata Party and the then-leader of the Janata Party, who spent months behind bars during the Emergency.

After the Emergency was abolished, Advani’s statements are still fresh in everyone’s mind in India. He said to the press, “You were only asked to bend, but you crawled.”

The Beginning of Ownership

Mrs. Gandhi had established a commission to look into the ownership structure of newspapers a year earlier, indicating her ambition to dominate the print media. This was obviously a ploy to retaliate against newspaper proprietors who were against her. Her party had a strong tradition of mistrusting the media, especially among its left-wing leaders. It was also a family characteristic; both her father Jawaharlal Nehru and her husband Feroze Gandhi were outspoken opponents of “monopoly ownership” in the media. Nehru is credited with coining the iconic phrase “the Jute Press.”

Mrs. Gandhi had established a commission to look into the ownership structure of newspapers a year earlier, indicating her ambition to dominate the print media. This was obviously a ploy to retaliate against newspaper proprietors who were against her. Her party had a strong tradition of mistrusting the media, especially among its left-wing leaders. It was also a family characteristic; both her father Jawaharlal Nehru and her husband Feroze Gandhi were outspoken opponents of “monopoly ownership” in the media. Nehru is credited with coining the iconic phrase “the Jute Press.”

Contemporary Media and Ownership

Who controls the Indian media industry? That is a challenging question. We have numerous media organisations that are owned and managed by a wide range of associations, including corporate bodies, societies, trusts, private people and political parties. It is challenging to gather, let alone interpret, information about these companies and people since it is dispersed, outdated, and incomplete. Nevertheless, from the meagre information that is accessible, a few important elements of media ownership stand apparent.

- The fact that there are so many media companies and sources often hides the fact that a small number of firms consistently dominate certain markets and market sectors; in other words, the marketplaces frequently have an oligopolistic nature.

- The absence of limits on cross-media ownership suggests that certain businesses, groups, or conglomerates dominate markets both horizontally (i.e., across various geographic regions) and vertically (i.e., across various media such as print, radio, television, and the internet).

- A growing portion of the media in India is owned or under the influence of political parties and individuals which is as big a threat as the emergency censorship.

- The promoters and controllers of media groups have historically had stakes in a variety of other commercial endeavours and they still do, frequently utilising their media outlets to advance these. A few promoters have diversified into other (unrelated) enterprises using the money they made from their media ventures.

- The method in which sizable industrial conglomerates are acquiring direct and indirect interest in media companies is a sign of the growing corporatization of the Indian media. Additionally, there is an increasing convergence between those who make and distribute media material.

These patterns could be seen as instances of consolidation in a market where major firms have been heavily indebted over the past few years. The shake-out also represents an increase in ownership concentration in an oligopolistic market, which is resulting in the loss of heterogeneity and plurality.

Despite the rise of internet technology encouraging democratisation by allowing more user-generated content, the emergence of lobbies and oligarchies may be indicative of a more globalised but ‘regulated’ communication landscape. While the expansion of the internet has resulted in the dissolution of geographical boundaries and decreased levels of gate-keeping in monitoring information flows, paradoxically, the perceived rise in variety of thought has also been accompanied by the fall of traditional media which is now used by the ones in power to flaunt their activities and initiatives in the form of paid pieces.

Despite the rise of internet technology encouraging democratisation by allowing more user-generated content, the emergence of lobbies and oligarchies may be indicative of a more globalised but ‘regulated’ communication landscape. While the expansion of the internet has resulted in the dissolution of geographical boundaries and decreased levels of gate-keeping in monitoring information flows, paradoxically, the perceived rise in variety of thought has also been accompanied by the fall of traditional media which is now used by the ones in power to flaunt their activities and initiatives in the form of paid pieces.