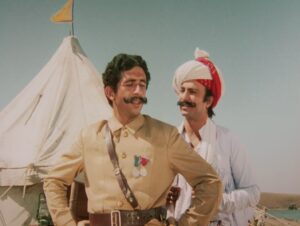

The four-page Chunilal Madia narrative Abhu Makrani and other tales of women defending themselves during colonial times that filmmaker Ketan Mehta heard while visiting Gujarat served as the inspiration for the plot of ‘Mirch Masala’. It effectively portrays rural pre-independence India and was released in 1987. It is a tragedy that throws light on the arrogance of petty officials, the crisis and tension brought on by desire and needless violence, the horrific triviality of colonialism, and the abuse and victimisation of women.

Where it begins

The movie makes it abundantly evident that men lose their human dignity and become animals when they are the only ones in charge and their power is unrestrained by the natural balance that results from the interaction of the sexes. In a fascinating scene near the lake at the start of the movie, Sonabai (Smita Patil) tells the recently arrived Subedar (Naseeruddin Shah) that water is meant for animals and village people. The Subedar then satirically but perversely refers to himself as ‘this animal’ and asks her to give him some. Then, in her capacity as a woman, she elevates him back to manhood:

The movie makes it abundantly evident that men lose their human dignity and become animals when they are the only ones in charge and their power is unrestrained by the natural balance that results from the interaction of the sexes. In a fascinating scene near the lake at the start of the movie, Sonabai (Smita Patil) tells the recently arrived Subedar (Naseeruddin Shah) that water is meant for animals and village people. The Subedar then satirically but perversely refers to himself as ‘this animal’ and asks her to give him some. Then, in her capacity as a woman, she elevates him back to manhood:

“As all men you shall bend and cup your hands.”

Corrupted love?

Naturally, the Subedar interprets this combative stance as an indication of the seduction game that turns love into a combat between two willing warriors, rather than as a declaration of the real social order. Even with its refinement, this kind of love—epitomized, for instance is not all that far from animality. The goal of the ‘game,’ which in this case refers to both play and prey, is to maximise the enjoyment of the hunt. Men view women as prey, and women view men as predators. Such corrupted game-making is largely responsible for our contemporary misinterpretation of what love is.

Women are treated as prey to be pursued after and captured; as a result, they must flee and use their fangs and claws to protect themselves. In a different section, the ‘Gandhian’ school teacher shows up at the Subedar’s camp with a crippled infant in his arms and laments that the boy was injured by his men’s horses as they were galloping through the hamlet.

Relevant intelligence

Ketan Mehta is an expert in his field. One of the film’s key topics is intelligence or common sense. For example, when the tax collector asks the village head, Mukhi (Suresh Oberoi), to bring him the woman he is longing for, he needs to provide him with ‘intelligence’; else, even though he ‘dislikes bloodshed,’ he would have to employ force. The Mukhi asks Sonabai for ‘wisdom’ while she is locked up in the factory and won’t open.

The issue with intellect and comprehension is that they are cultural traits that must be fostered and developed. It needs a supportive atmosphere to grow. When asked about India’s independence, the schoolmaster awkwardly concludes,

The issue with intellect and comprehension is that they are cultural traits that must be fostered and developed. It needs a supportive atmosphere to grow. When asked about India’s independence, the schoolmaster awkwardly concludes,

“What’s the use of it? How can we identify it?”

“You need to study to feel its value,” he argues.

Because contemplating one’s defeat is a necessary step towards liberation and independence. An animal forgets that his instincts have made him a slave. To some extent, this also applies to illiterate men.

Access to knowledge

The question of intelligence naturally relates to the theme of women’s emancipation, and it’s interesting to note the excuses offered by other women to condemn the Mukhi’s wife Saraswati (Deepti Naval) when she brings her daughter to the Gandhian schoolmaster’s class (thus being called ‘mad’); these excuses include

“No one will want to marry her!” and

“School won’t help the girl become a lady.”

Thus, there is a statement on women’s access to knowledge that runs counter to what the movie implies about women’s resistance to men’s dominance. Instinct or even feminine intuition is insufficient. Indeed, Saraswati and Sonabai are two representations of strong women.

Radha’s Tale

This may also be seen in Radha’s tale, which functions as a kind of counterpoint to Sonabai’s. A young lady named Radha has been engaged to the brother of the Mukhi. Sonabai differs from the Subedar in that she gives in to his passion one night in exchange for a small token that she displays Sonabai while they are both within the factory’s closed doors. Radha makes an attempt to persuade Sonabai that accepting a night with the bully will result in something positive—namely, her release from the factory’s hazardous confines.

We comprehend that the little girl may have lost her lover that night, despite everything else. Radha’s father visits the Mukhi and pleads in vain for his brother to be allowed to marry her. However, the happiness of two young people is not worth the calmness of the community, and if pressure is too high, a young woman’s virginity can even be exchanged by other women.

The concept of self- respect

By the way, ‘self-respect’ is the idea that is considered a womanly virtue. When the soldiers ask him to turn over the young woman who is running, Abu Miyya, the old factory guard (Om Puri), is defending Sonabai’s self-respect. At the Mukhi’s village meeting, an old villager alludes to the women’s self-respect after some human dignity has returned to the minds of those in attendance.

Paradoxically, when the Subedar talks of Sonabai moving inside his tent, he also says that his “self-respect is at stake.” What ‘self’ is meant here if one ignores this haughty mocking of genuine virtue, which the Subedar voluntarily degrades? What does the movie teach us about the integrity of women? Why does one woman see her body as open to a stranger, while another will stop at nothing to avoid being unfaithful? One of the ladies tells Sonabai,

Paradoxically, when the Subedar talks of Sonabai moving inside his tent, he also says that his “self-respect is at stake.” What ‘self’ is meant here if one ignores this haughty mocking of genuine virtue, which the Subedar voluntarily degrades? What does the movie teach us about the integrity of women? Why does one woman see her body as open to a stranger, while another will stop at nothing to avoid being unfaithful? One of the ladies tells Sonabai,

“Only the rich can afford to have self-respect.”

What’s remarkable is that the movie’s concept of self-respect sparks a conversation about what it means to be a guy. Regarding his unwillingness to open the door, Abu Miyya, for example, remarks,

“There is at least one man in this village.”

Previously, another villager said that it was women, not men, who were the cowards at the village meeting. Therefore, asserting one’s self-respect is not only more human; it is also macho, in the sense of bravery. It is establishing certain boundaries for oppression and alienation. It is implying that the self is similar to a fortified city or temple, where doors open to gentle critics but close to bullies.

Previously, another villager said that it was women, not men, who were the cowards at the village meeting. Therefore, asserting one’s self-respect is not only more human; it is also macho, in the sense of bravery. It is establishing certain boundaries for oppression and alienation. It is implying that the self is similar to a fortified city or temple, where doors open to gentle critics but close to bullies.

It is prepared to be under attack and to give up its own freedom of movement in order to preserve the larger freedom of spirit. The movie claims that while money or position are not important factors, education is, at least in part. Saraswati and Sonabai are two examples of women who are resisting and constructing a better world for tomorrow.

Why Mirch Masala?

Mirch masala, the fiery red spice that is so important to the movie’s theme. The Subedar refers to Sonabai as “hot stuff,” and for once he’s not wrong, even though the phrase has a slight connotation. I think Ketan Mehta picked this term to symbolise the fire energy of Indian women—or, at the very least, the spirit that these women must develop in order to rebel against oppression and false civilization. The hue red is associated with revolution, blood, and femininity. It is possible to interpret this title as a subtly critical assessment of the tasteless masala films that, too frequently, fail to challenge the tenets of the Indian social order, particularly with regard to the status and prospects of women.