–An Article by Poojan Patel

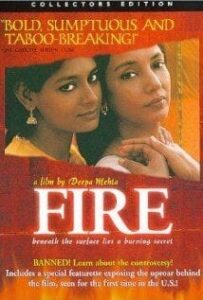

In a conservative and patriarchal society, where discussions about sexual orientation and gender relationships were, and in many ways still are, deemed taboo, Deepa Mehta’s “Fire” burst onto the scene almost two decades ago, setting the silver screen ablaze with its audacious portrayal of homosexual love. The film, which explored the clandestine romance between two sisters-in-law trapped in traditional roles, quickly became a cultural landmark in Indian cinema, defying conventions and sparking a wave of social and political discourse.

Mehta’s direction and script work in sync to create a film that is not just aesthetically appealing but also intellectually interesting. The narrative moves at a leisurely pace, allowing for the slow development of characters and relationships. Mehta’s ability to convey the intricacies of human emotions and feminine sexuality is admirable.

“Fire” begins its journey with a powerful statement, as young Radha yearns to see the ocean, to which her mother cryptically responds, “What you can’t see, you can see.” It’s a subtle foreshadowing of the unconventional love that will define Radha’s life, a love that defies societal norms and expectations. Radha, portrayed by the brilliant Shabana Azmi, is a “barren” woman, imprisoned in her role as caretaker, wife, and homemaker. Her inability to bear children shackles her to a life of servitude, her identity defined solely by her husband’s needs.

Sita, played with grace by Nandita Das, represents the antithesis of the traditional Indian wife. She is a modern woman, imprisoned in a loveless marriage, yearning for a connection that transcends the societal shackles that constrain her. Her husband, Jatin, sees her as little more than a means to satisfy his own desires, reflecting a disturbingly pervasive view of women in society.

The movie also confronts the age-old sayings and proverbs that have contributed to the marginalization of women. The belief that “a woman without a husband is like plain rice: bland and unappetizing” reflects the deeply ingrained notions of femininity and women’s worth in Indian society. Radha’s response that she enjoys bland rice hints at her discontent with her marriage and a desire to break free from societal constraints.

The movie also confronts the age-old sayings and proverbs that have contributed to the marginalization of women. The belief that “a woman without a husband is like plain rice: bland and unappetizing” reflects the deeply ingrained notions of femininity and women’s worth in Indian society. Radha’s response that she enjoys bland rice hints at her discontent with her marriage and a desire to break free from societal constraints.

The film delves into the theme of female sexuality, exposing the harsh reality of women’s lack of control over their own desires. It highlights how women are reduced to mere objects, expected to conform to traditional gender roles. The stark difference in the portrayal of heterosexual and homosexual intimacy is striking. Heterosexual encounters are depicted as mere acts of penetration, void of foreplay and emotional connection, while the love between Sita and Radha is portrayed as sensual, romantic, and focused on female pleasure.

“Fire” doesn’t shy away from addressing the suppression of female sexuality in a patriarchal society. It illustrates how women are denied agency over their own bodies and desires, perpetuating the stereotype that a woman’s role is limited to serving her husband and family. The film incisively highlights society’s hypocrisy in simultaneously imposing and condemning women’s sexuality. “Fire” remains a stark critique of oppressive norms, challenging viewers to question and dismantle the societal structures that shackle women’s freedom and potential.

“Fire” doesn’t shy away from addressing the suppression of female sexuality in a patriarchal society. It illustrates how women are denied agency over their own bodies and desires, perpetuating the stereotype that a woman’s role is limited to serving her husband and family. The film incisively highlights society’s hypocrisy in simultaneously imposing and condemning women’s sexuality. “Fire” remains a stark critique of oppressive norms, challenging viewers to question and dismantle the societal structures that shackle women’s freedom and potential.

The film loosely draws inspiration from Ismat Chughtai’s story, “Lihaaf,” and presents a poignant portrayal of homosexuality in a society that remains largely intolerant. It sheds light on the lives of women who denied the love and fulfillment they deserve, and find solace in each other’s arms. However, it is unsettling that their exploration of sexuality arises from the unhappiness of their failed marriages, highlighting society’s tendency to stigmatize women who dare to embrace their desires.

The choice of names, Radha and Sita, invokes Hindu iconography, symbolizing the purity of their love in the face of societal condemnation. The film draws parallels with the mythological tale of Sita walking through fire to prove her purity to Lord Rama. Similarly, when Radha’s saree catches fire during a confrontation with her husband, it becomes a metaphor for their love’s purity, despite society’s condemnation.

The choice of names, Radha and Sita, invokes Hindu iconography, symbolizing the purity of their love in the face of societal condemnation. The film draws parallels with the mythological tale of Sita walking through fire to prove her purity to Lord Rama. Similarly, when Radha’s saree catches fire during a confrontation with her husband, it becomes a metaphor for their love’s purity, despite society’s condemnation.

“Fire” remains a cinematic milestone in the history of Bollywood, daring to shed light on love within the confines of a traditional family setting. It confronts the harsh reality that the suppression of female sexuality is not a reflection of women’s lack of desire but rather a result of society’s denial of their agency.

In a society where traditions and norms continue to dictate the lives of women, “Fire” stands as a beacon of change, sparking conversations that were long overdue. It’s a testament to the power of cinema to challenge societal conventions, ignite dialogue, and pave the way for a more inclusive and understanding world. “Fire” remains a relevant reference point in the ever-evolving discourse on gender relationships in India and a reminder that love knows no bounds, defying societal norms with its undeniable, passionate flame.