Elephants take center stage in Indian culture. They serve as a testament to the interconnected history, culture, and society of India and, by extension, to Hinduism and Buddhism. Its embodiment may be seen in symbolism, as well as in its fundamental presence in history, Puranas, and daily life. Numerous texts have been written exclusively about elephants since they are revered as sacred animals.

Buddha as Vessantara

The queen announced she was expecting the day after having a dream about an elephant entering her womb. That foetus developed into Buddha. According to the Jatakas, Buddha was Vessantara, prince of Sivi, who had a magical elephant that summoned showers of rain wherever it went. As a result, when Kalinga experienced a drought, the monarch asked that Vessantara’s elephant be transported there to bring in rain.

The queen announced she was expecting the day after having a dream about an elephant entering her womb. That foetus developed into Buddha. According to the Jatakas, Buddha was Vessantara, prince of Sivi, who had a magical elephant that summoned showers of rain wherever it went. As a result, when Kalinga experienced a drought, the monarch asked that Vessantara’s elephant be transported there to bring in rain.

These types of tales make it quite evident that elephants are connected to rain and fertility in South East Asia, including India. The presiding god, Jagannath, is decorated with an elephant mask in Puri, Orissa, during the height of summer in the hopes that it will act as a jewel and usher in the monsoons sooner.

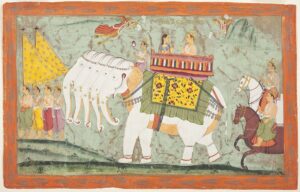

Indra’s Airavata

It should come as no surprise that Indra, the sky god and lord of the gods, is pictured riding an elephant. Not your typical elephant, but Airavata; a white-skinned elephant with six trunks and six pairs of tusks. The monsoon clouds, which can be imagined as a herd of dark elephants, are struck by Indra’s thunderbolt as he rides Airavata into battle and causes them to pour rain, turning the red land green. There is no question that Indra’s white elephant represented the white clouds that adorn the sky after the rain clouds have passed because Airavata has names like “the wandering cloud” and “the brother of the sun” among his numerous titles.

It should come as no surprise that Indra, the sky god and lord of the gods, is pictured riding an elephant. Not your typical elephant, but Airavata; a white-skinned elephant with six trunks and six pairs of tusks. The monsoon clouds, which can be imagined as a herd of dark elephants, are struck by Indra’s thunderbolt as he rides Airavata into battle and causes them to pour rain, turning the red land green. There is no question that Indra’s white elephant represented the white clouds that adorn the sky after the rain clouds have passed because Airavata has names like “the wandering cloud” and “the brother of the sun” among his numerous titles.

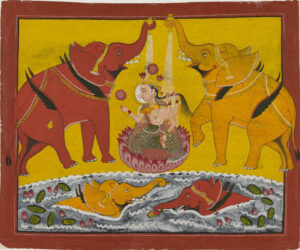

Gaja Lakshmi

According to the Kurma Purana, Airavata was one of the fourteen riches that were revealed when the gods churned the ocean of milk. He was the first elephant, and Indra claimed him. Since that time, elephants have represented regal authority. When the gods stirred the ocean of milk to welcome Lakshmi, the goddess of wealth, they brought together these eight elephants, each of which was white, signifying their celestial nature. She was doused with water when they raised their trunk. This was part of the abhishek, which involves pouring water and symbolises rain. Rain brings greenery, and vegetation brings riches, and wealth brings power. Elephants are therefore linked to fertility, prosperity, and power. It is Lakshmi’s preferred animal. As she rides on it, she bestows blessings on the earth’s kingdoms.

According to the Kurma Purana, Airavata was one of the fourteen riches that were revealed when the gods churned the ocean of milk. He was the first elephant, and Indra claimed him. Since that time, elephants have represented regal authority. When the gods stirred the ocean of milk to welcome Lakshmi, the goddess of wealth, they brought together these eight elephants, each of which was white, signifying their celestial nature. She was doused with water when they raised their trunk. This was part of the abhishek, which involves pouring water and symbolises rain. Rain brings greenery, and vegetation brings riches, and wealth brings power. Elephants are therefore linked to fertility, prosperity, and power. It is Lakshmi’s preferred animal. As she rides on it, she bestows blessings on the earth’s kingdoms.

In Erotic Literature

Kamasutra

Elephants are representations of untamed, primal sexual force in erotic literature. The Kamasutra describes an elephant-woman, also known as a Hastini, as the lustiest of women who is also crude and vulgar in her demeanour.

Mahabharata

Queens like Draupadi were referred to in the Mahabharata as Mada-gaja-gamini, or “women who walk like cow-elephants in rut.” Although the translation may not convey a positive image, it basically describes a large-hipped, voluptuous, and graceful woman. Indian poets like Kalidasa have drawn inspiration from an elephant’s gait and hip-swinging motion for aeons. An elephant moves silently and delicately on the ground, planting its feet with great care.

Queens like Draupadi were referred to in the Mahabharata as Mada-gaja-gamini, or “women who walk like cow-elephants in rut.” Although the translation may not convey a positive image, it basically describes a large-hipped, voluptuous, and graceful woman. Indian poets like Kalidasa have drawn inspiration from an elephant’s gait and hip-swinging motion for aeons. An elephant moves silently and delicately on the ground, planting its feet with great care.

Vishnu Purana

Vishnu saves Gajendra, the elephant king, from a crocodile’s teeth. The king of elephants, surrounded by cow-elephants, is a metaphor for the world’s sensual pleasures, with the crocodile standing in for materialism’s shackles. Liberation occurs when the elephant (sexual power) extends its trunk and presents the Lord with a lotus (devotion).

Bhagavat Purana

Kamsa sends Kuvalayapida, the regal elephant, to tread Krishna. In addition to killing the elephant, Krishna takes its tusks as a victory trophy. The cowherd declares open rebellion against the monarch by killing the elephant.

Kamsa sends Kuvalayapida, the regal elephant, to tread Krishna. In addition to killing the elephant, Krishna takes its tusks as a victory trophy. The cowherd declares open rebellion against the monarch by killing the elephant.

Tantrik Literature

The goddesses are frequently depicted riding elephants or holding impaled elephants in their palms in Tantrik literature. This proves the deities’ power over people in a sexual and violent way.

Derivations

The elephant is unstoppable and highly deadly when it is in heat, or musht. From this emerged slang terms that the youth use, like masti. An elephant will exude fluid from its temples when it is at the height of its sexual cycle. This is referred to as mada, from which the word madira for wine is derived.

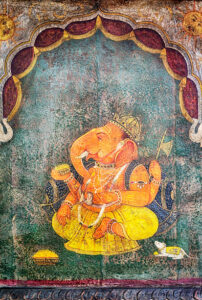

Given that the god is known as the elephant-headed Ganesha in India.

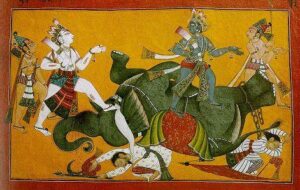

The Supreme Ascetic

Elephants shouldn’t matter to ascetics if they stand for riches, power, and material grandeur. They also don’t. Shiva is known as Gajantaka, the supreme ascetic, because he killed an elephant, flayed it alive, and then used its thick skin, known as Gaja-charma, as a garment. Many religious texts depict the elephant as the terrifying demon Gajasura, a clear metaphor for the perils of sensuous desires. Elephant skin is difficult to tan. It then rots. Shiva furthers his image as someone who despises all things material by donning it.

However, as Hinduism developed in India, Shiva’s elephant-headed son replaced the demon with an elephant head that had been slain by the passage of time. Why did Shiva use an elephant’s head to raise the offspring that his partner, the goddess Shakti, had independently created? He gave his assistants the following directive: “Go north and fetch the head of the first living thing you come across.”

According to the Brahmavaivarta Purana, the white Airavata, Indra’s mount, was the first creature that Shiva’s attendants saw. The North is considered to be the direction of growth in Vaastu. It is obvious that the elephant murderer is using the pinnacle of material opulence to create his son. Shiva ceases to be the hermit who rejects the world and changes into Shankara, the householder who embraces the world, in the process of producing the elephant-headed Ganesha. Thus, the elephant spreads life and development wherever it travels.