“अरे! हम हैं तो समाज हैं। और इतनी ही फिकर हैं तो मर्दो को बांध के रखो ना घर पे| मर्द खरीदता है तभीच तो औरत बेचती हैं अपनेआप को।”

With the pace of an elderly, weary woman, Rukminibai (Shabana Azmi) thunders while pulling her loose पल्लु over her breast with the unabashed sultriness of a former courtesan. She then requests a song from Zeenat (Smita Patil), the treasured virgin of the brothel, to relieve her concerns as the matriarch of a home that is continuously challenged by the patriarchal society outside its doors.

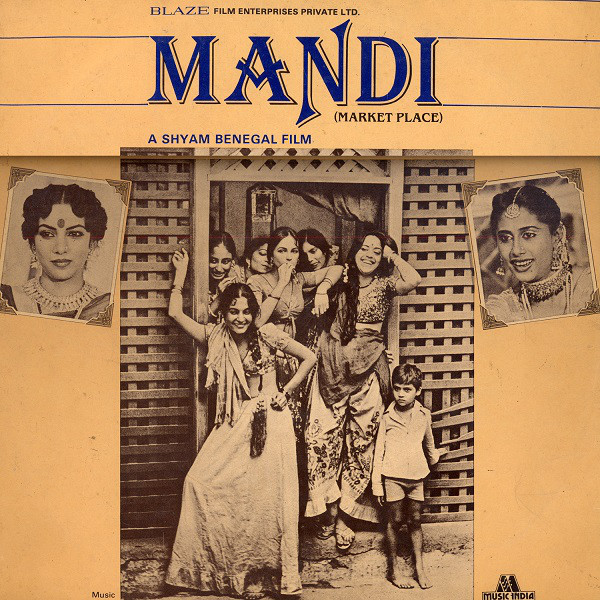

The premise and its story

Mandi tells the tale of this feisty old madame of a brothel and her ‘girls’ who struggle to survive on their matriarchal island in the midst of a patriarchal society that relentlessly attempts to undermine the sanctity of a place where women are free from the social, economic, and sexual mores that are imposed by the patriarchal, middle class morality.

The story’s basic premise is taken from Ghulam Abbas’ short story “Anandi,” but Shyam Benegal adds a number of levels of complexity that Abbas opted to omit. Characters from the “civilised,” patriarchal society principally try to undermine Rukminibai’s growing “mandi” of sensual pleasures in the plot.

Why sensual pleasures?

The women of the brothel take great pleasure in their abilities as courtesans in addition to being competent sex workers who can satisfy their clients’ sexual desires.

“हम लोगा कलाकारा हैं| हमारी कला में ही तो हमारी जान बस्ति हैं|” In her archaic Urdu accent, Rukminibai proudly declares. Every lady has had classical dance and music training, but Zeenat stands out for her रियाज़, singing ठुमरी and ख़याल, dancing, and acting, which gives the impression that the brothel is an artistic refuge away from the uncouth masculinity of the outside world.

On hearing Asha Bhosale’s accurate portrayal of all of Zeenat’s ग़ज़ल performances, one may believe Rukminibai’s claim that they are the only keepers of the vanishing art of court music and poetry. The soundtrack of Vanraj Bhatia, which features Hindustani classical music and Urdu ग़ज़लs compositions by शायरs like Mir Taqi Mir, soothes the harshness of the realities that the film depicts while highlighting the feminine and artistic Mandi.

The ‘evil’, the ‘immoral’?

All the women from the brothel are unashamed of their work, which is one of their most appealing and rebellious characteristics. When the municipal committee unanimously decides to kick them out of the brothel or when Shantidevi, a social activist, shows up at their doors with her morals and a servile group of supporters to stop the ‘immoral’ and ‘evil’ Rukminibai from holding Phoolmani, the newest addition to the girls, captive, they admit that their work is a necessity for their financial survival and refuse to leave. Rukminibai’s market admits to being one in all its harshness, but the patriarchal market outside sells women’s silent misery for profit.

Sociological observations

A number of comparisons Benegal draws between Rukminibai’s matriarchal brothel and the self-righteous, patriarchal world at large form the basis of the film’s sociological observations and critique.

The two ‘mandis’ are the main contrast. In his narrative, Abbas refers to both the “moral” patriarchal market that deals with people’s lives and happiness and the “ज़नान-ए-बाज़ारी” or “market place of women.”

The hegemonic power structure

Rukminibai has not yet placed Zeenat, the sought-after virgin of the brothel, on the market because she is awaiting the ideal client to show up and make her greedy appetite satisfied. The newest member of Rukminibai’s girls, Phoolmani, is coerced into staying at the brothel and forced to have sex with a customer when she obviously is not ready for it; Tungrus, the servant and ironically enough, the only man in the house, runs around being insulted and kicked around by all the women. Everyone is a victim of the brothel’s power structure.

Everyone follows Rukminibai’s decision, whether they like it or not. Each and every one of these violations of these people’s rights is a sign that even the most well-intentioned political structures have the capacity to be repressive. Benegal never downplays the shortcomings of this matriarchal culture while highlighting its positive aspects.

The male gaze

But when compared to the harsh, inhumane marketplace of the patriarchal world, these transgressions seem excusable. Except for Susheel (Zeenat’s lover) and their regular doctor, any man who enters the brothel takes away from these women some of the economic, social, or sexual agency they have established for themselves. The girls, on the other hand, are unapologetic, unafraid, and take advantage of their sexuality in their relationships with these males. When males try to manipulate them, women respond by pleading for mercy or, if necessary, physically assaulting them. They use every trick in the book to influence these folks in their favour.

The forced deals

The ‘deal’ between Mr. Gupta (Kulbhushan Kharbanda), a wealthy and lecherous contractor, and Mr. Agarwal (Saeed Jaffrey), the insolvent municipal chairperson, is just one example of how market-like the patriarchal world is. They gang up together to depose Rukminibai from her brothel, demolish it, and replace it with a commercial complex, splitting the proceeds. They finalise this ‘contract’ by choosing to wed their kids without ever asking them first. Susheel, the boyfriend of Zeenat, is the son of Mr. Agarwal. Malati is the shy, spoilt daughter of Mr. Gupta. These two are the sought-after virgins, simply commodities traded in this dealing.

Since Malati is coerced into a relationship against her will, her fate is equally as terrible as Phoolmani’s. The women in this situation do not even have the freedom to advocate for themselves or exercise any type of autonomy.

Wo‘man’ for Women?

Even a woman in a position of authority, such as Shantidevi, behaves in a very ‘male’ and power-hungry way to uphold patriarchal morals. Despite her well-intended statements that she cares about the well-being of women in her community, she refuses to acknowledge the sex workers’ dire financial situations. In a meeting of the local council, she instead decides to vote in favour of moving the brothel to the outskirts of the city.

Her ‘democratic’ movement has definite feudal undercurrents. Her attitude towards the attendees of her own rally is incredibly degrading. When the time for the actual discussions with Rukminibai comes, she expects to address the clamouring crowd from atop a literal and symbolic pedestal and then she won’t let any of them in. She obviously thinks she is superior to the crowd of people swarming around her. She resembles a feudal overlord dressed as a social justice activist.

Double crossing characters

Benegal depicts these two utterly distinct worlds and emphasises how challenging a reconciliation would be by attempting to unite them through Zeenat and Susheel’s romance. In his financial transaction with Mr. Gupta, Mr. Agarwal utilises Susheel as an asset while Rukminibai commercialises Zeenat’s virginity. Both are used as commodities by the power systems to which they belong, but more significantly, neither is conscious of the connection between them.

Zeenat is the love child of Mr. Agarwal and one of the sex workers of Rukminibai’s brothel. Due to these circumstances, Susheel and Zeenat’s blossoming romance—which starts at a party Mr. Gupta threw to announce Susheel’s engagement to Malati—is improbable from the start. Nevertheless, they keep on loving each other despite their differences. Zeenat ends up killing herself before her matriarch. Their rebellious love’s tragic destiny serves as a stark reminder of how monstrous and unbeatable the ingrained power systems of a “mandi” can be.

Ode to the details

More than any of the movie’s profound societal critique, Mandi’s attention to detail is what would win your heart.

In his attempt to capture the greater social reality, Benegal never omitted the minute, everyday elements that were nonetheless important from the lives of these characters. Rukminibai doing the daily “पूजा” and carrying the “धुप” around her home while humming a folk song; Tungrus carrying tea for all the women or massaging Vasanti’s back as she took a bath. Zeenat smoking her hair out over a wicker basket with coal and camphor; Nadira, who is fiercely sexual and fiercely protective of all the other women; Vasanti and Ram Gopal, the sleazy photographer’s little romance; one of the brothel girls singing a lullaby to her child. Even though each of these sequences appeared to be minor in the overall story about the numerous structural issues that plague our society, they will make you feel content and joyful as a viewer.

Benegal concentrated and occupied these moments with brief but significant pauses so that the audience may witness each unique moment from the lives of his characters and fully appreciate their humanity and normalcy. It gives the viewer an opportunity to make observations instead of using the pompous dialoguebaazi, native to mainstream cinema of the 1980s.

The incredible cast

Naturally, a large portion of the credit for the sincerity and honesty of the portrayal also goes to the incredible cast, from Shabana Azmi and Smita Patil, who dominate the story, to Soni Razdan and Naseeruddin Shah, who play the smallest roles with an accuracy and dedication that brings this messy, dark, yet oddly humorous world to life on screen. The film is sort of a sarcastic view of the obvious defects in society that we, as its upstanding inhabitants, choose to ignore.

A film like ‘Mandi’ becomes especially significant at a time when Indian middle class morality is growing more rigid and retrograde because it exposes the glaring hypocrisy of our so-called “civilised” society. The variety of realities and identities that exist in what they would prefer to be a unified society are made clear to its viewers.

A film like ‘Mandi’ becomes especially significant at a time when Indian middle class morality is growing more rigid and retrograde because it exposes the glaring hypocrisy of our so-called “civilised” society. The variety of realities and identities that exist in what they would prefer to be a unified society are made clear to its viewers.