An Article by Poojan Patel

Christmas, one of the most widely celebrated holidays worldwide, has a rich history that traces back to a blend of Roman winter solstice festivities and early Christian traditions. While the first documented Christmas celebration in Rome dates back to the year 336, the specifics of these early festivities remain shrouded in mystery. In lieu of potentially inaccurate details, we will explore fascinating facts about the development of Christmas traditions, influenced by Roman practices and the solemn early Christian observances.

Roman Influence:

The roots of Christmas celebrations can be traced to the Roman festival of Saturnalia or or Dies Natalis Solis Invicti, a week-long extravaganza characterized by gift-giving, feasting, and a general atmosphere of revelry. This festival, occurring in late December, likely played a pivotal role in shaping early Christmas traditions. Furthermore, the decision to celebrate Christmas on December 25th is believed to be connected to the birthday celebration of the Roman sun god Mithras, reflecting the assimilation of pagan practices into the emerging Christian holiday. During this holiday, Romans celebrated the rebirth of the sun, and similarities to Christmas include the decoration of small trees.

Despite the scanty evidence, there has long been conjecture that these Roman celebrations are where Christmas got its start. For example, Scottish anthropologist Sir James George Frazer noted in his hugely successful book “The Golden Bough”, first published in 1890, that there were parallels between these paganic feasts and Christmas. It is uncommon for contemporary anthropology courses to teach Frazer’s work, and you’ll discover that shockingly few academic articles reference it. Anthropology and the Science of the Supernatural: Souls, Ancestors, Ghosts, and Spirits by VanPool and VanPool (2023) provides a partial overview of Frazer’s absence in contemporary anthropology.

Early Christian Practices:

Though the origins of Christmas celebrations may be traced back to the fourth century AD, the holiday truly came into its own during the late medieval era. In English text, the word “Christmas” first appears in the 12th century AD. Additionally, some of the contemporary customs date back to the 1500s. For example, turkeys were first connected to Christmas dinners in 1573, which is 150 years earlier than they were to American Thanksgiving dinners. In addition, presents were bestowed upon “good people” and the “wicked” received punishment during the Middle Ages. Sham fights ensued, which used to be a festive custom.

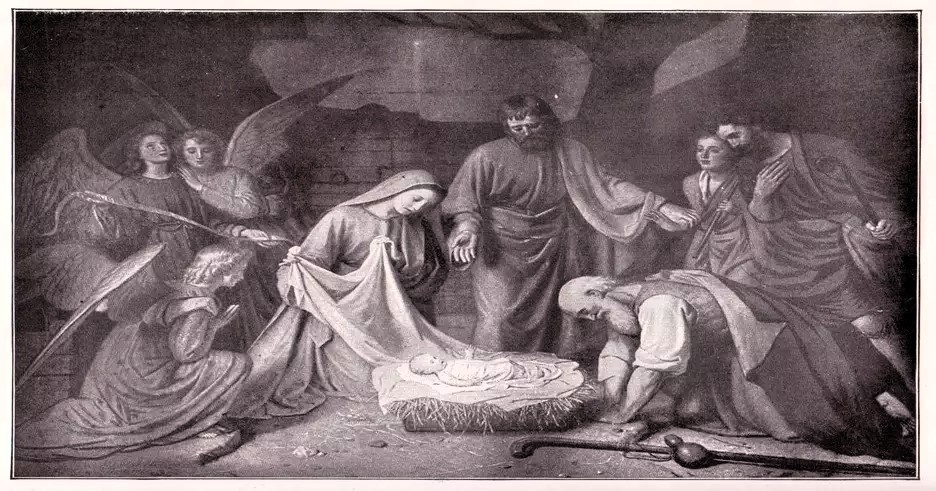

In the early years of Christianity, believers commemorated Jesus’ birth through solemn vigils and feasts on December 25th. These celebrations were markedly different from the later, more secular merriment associated with Christmas. The focus was on religious observances, emphasizing the spiritual significance of the event rather than the festive customs that would later become integral to the holiday.

Particularly in America, Germany, Scotland, and England, devout Christians opposed and canceled the medieval Christmas. The boisterous nature of the celebration, which frequently involved binge drinking that frequently resulted in fights rather than cheering, contributed to this resentment. Nonetheless, religious prohibitions on the celebration might have also resulted from the introduction of Father Christmas, a legendary figure who originated in England in the fifteenth century. The Church of England attempted to do away with Father Christmas and restore Christmas as a time to honor Christ in the 16th and 17th centuries. Father Christmas eventually blended with the idea of Santa Claus. Perhaps the opposition against Christmas was largely effective.

Gradual Evolution:

The introduction of Santa Claus to the New World by German and Dutch settlers during the 18th and 19th centuries marked a departure from the traditional figure of Father Christmas. Unlike the symbolic and mythical nature of Father Christmas, Santa Claus is believed to be inspired by Saint Nicholas, a 3rd-century AD individual who, according to legend, overcame orphanhood, inherited significant wealth, and devoted himself to altruism. While the story of Saint Nicholas likely contains elements of historical truth, embellishments have accumulated over time. Steven Hales, in his 2010 article “Putting Claus Back in Christmas,” emphasized the mixed nature of this narrative. The inclusion of Santa Claus in Christmas celebrations has sparked debates, with critics expressing concerns about commercialization and the dilution of the holiday’s essence, while proponents argue that Santa serves as a Christian allegory, teaching children the value of selfless giving. Despite controversies, Santa Claus remains a beloved symbol, embodying the spirit of generosity and simple joy during the festive season.

Christmas traditions underwent a gradual evolution over centuries, assimilating elements from diverse cultures and regions. Gift-giving, a prominent feature of modern Christmas celebrations, found its roots in the Roman Saturnalia tradition. Decorations, carols, and feasting also became established customs over time. The amalgamation of these diverse influences contributed to the multifaceted nature of Christmas as we know it today.

Christmas, with its blend of Roman and Christian influences, has evolved into a diverse and cherished celebration. While the specifics of the earliest festivities remain elusive, the amalgamation of traditions over centuries has given rise to a holiday that transcends religious boundaries and cultural differences. Understanding the historical development of Christmas allows us to appreciate the rich tapestry of customs that contribute to the festive spirit of the season.